“Let’s pretend the glass has got all soft like gauze, so that we can get through. Why it’s turning into a sort of mist now, I declare! It’ll be easy enough to get through.”

—Lewis Carroll, Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There1

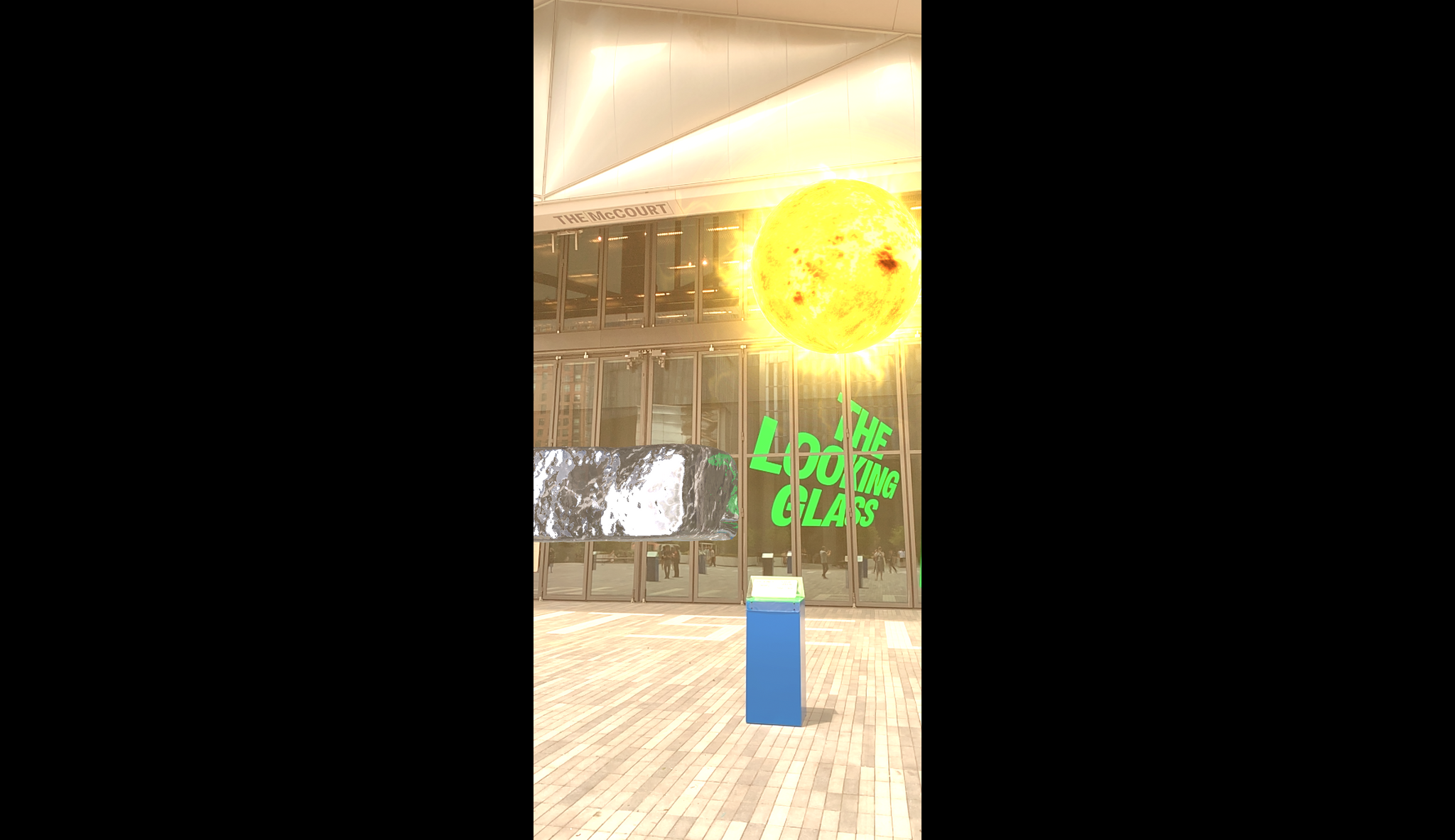

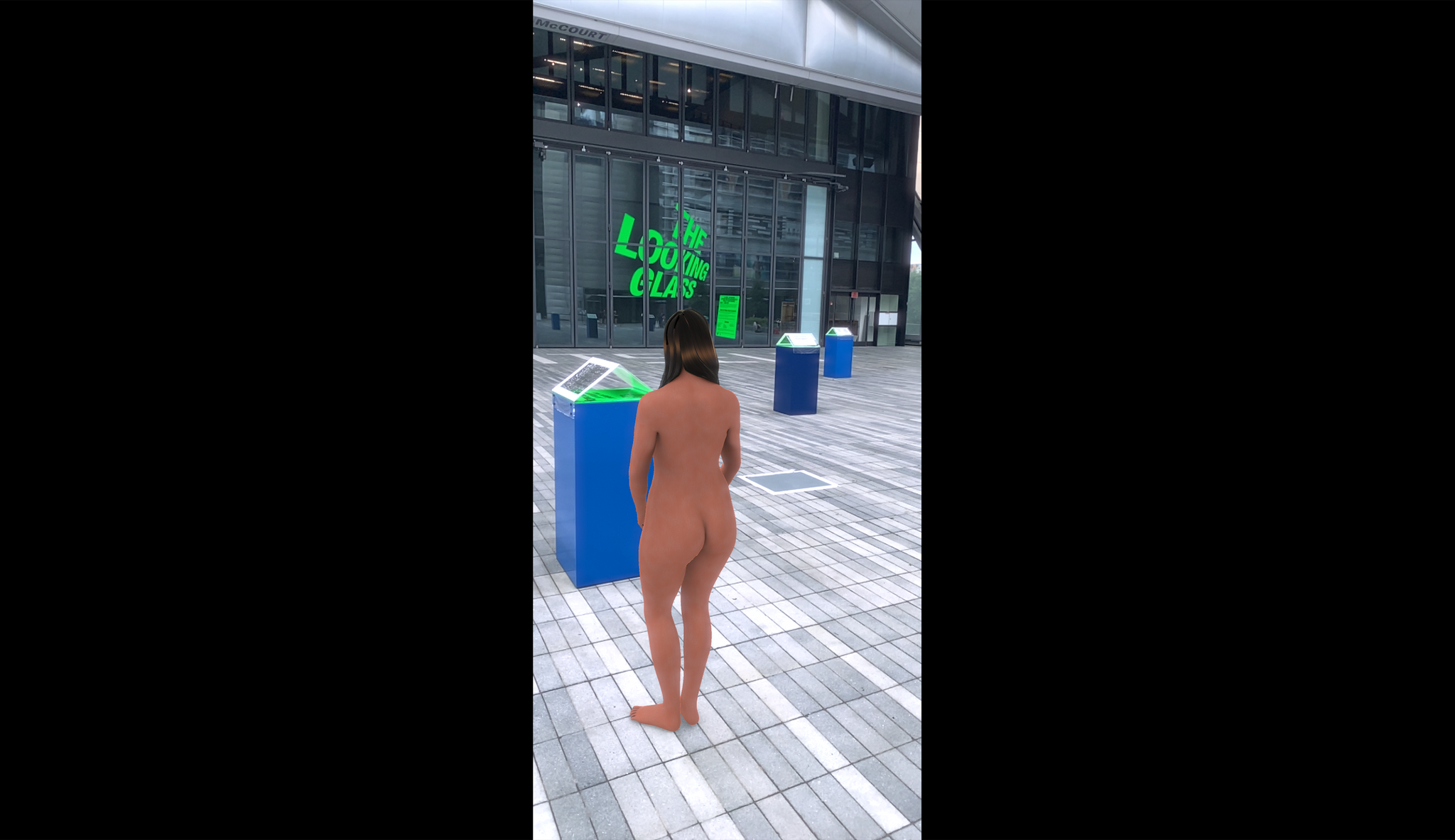

The Looking Glass is an exhibition of 21 augmented reality (AR) artworks by 11 artists—Nina Chanel Abney, Darren Bader, Julie Curtiss, Olafur Eliasson, Cao Fei, KAWS, Koo Jeong A, Alicja Kwade, Bjarne Melgaard, Precious Okoyomon, and Tomás Saraceno—installed at The Shed and on the High Line. While the works in this show are no doubt real, unlike in other exhibitions, they are not tangible objects. Invisible to the naked eye, they come to life on your phone’s screen through the Acute Art app when you stand in the right spot. Once caught on camera they appear as real as the environment around them. Through the juxtaposition of physical and virtual worlds, they convey a sense of surprise and wonder. Some of them appear as mischievous tricks, some as awe-inspiring materializations of other worlds. They can easily be documented and shared with friends and will no doubt have a life of their own on social media. These are the new possibilities of AR technology.

Beginning with the 19th century’s so-called “fathers of photography,” including Louis Daguerre, Henry Fox Talbot, and others, the way we see and understand images, how they are produced and circulated, increasingly came to define the experience of living in the 20th century. With the advent of new media and such ways of seeing as augmented and virtual reality aided by machine learning, this century has continued this trajectory. The Shed, as a new institution of and for the 21st century, is the ideal institution to consider how this new way of seeing will be explored and put to use by the artists of our time.

In 1927, Marcel Duchamp, an artist who worked ahead of his own time, discovered that his glass-panel artwork The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (1915 – 23), often called The Large Glass, had been cracked after it was dropped in shipment. The effects of this chance accident pleased the artist, and he left the cracks as an integral part of the work. Recently, writer and theorist Sanford Kwinter has suggested that the piece, in its play of transparency and reflection, was prophetic of virtual space that would eventually be opened by today’s technology. “The history of every art form,” the German philosopher and cultural critic Walter Benjamin observes, “shows critical epochs in which a certain art form aspires to effects which could be fully obtained only with a changed technical standard, that is to say, in a new art form.”2

For Kwinter, Duchamp’s work becomes a manual for understanding the rest of 20th-century art:

The initial trope that animates it philosophically is that The Large Glass is not only full of opaque entities, and images; it is also a transparency. The standard dogma is that in any situation, as in the gallery or the museum, the spectators become part of the activation of The Glass. When you peer at it, not only do you encounter reflections of yourself looking, but your gaze also passes right through it; you behold the other spectators, indeed an entire aesthetic-experiential ecology. The Large Glass thus operates as a manual of 20th century aesthetics.3

One might conclude that Duchamp anticipated the possibilities that have developed in the 21st century, too. Today, almost all of us carry miniature versions of that glass, imbued with the power to open virtual space, in our pockets and spend a considerable part of our lives engaging with it. Did he even foresee that the glass on our smartphones would break in ways that resemble what he referred to as his “delay in glass,” permanently installed at the Philadelphia Museum of Art? Kwinter believes so: “I would further argue that we live in a universe where The Large Glass is intimately sutured into our nervous systems.” He spells out the consequences:

Let us not imagine that our computer screen is anything other than “a large glass”; it is not. If you consider the environment that we engage with, if we account for our screen time and the promiscuity of connections that it permits, we realize that we are now living in The Large Glass. And yes, it is a nightmare because we cannot exit it.”4

Some of the works overwhelm, like Saraceno’s massive spiders. Others elude us, as does Curtiss’s nude woman who forever turns her back toward the viewer. Will we ever see her face? Koo Jeong A’s minimal cube refracts the sunlight and reflects its environment. Cao Fei’s little boy, taken from her film Nova, has escaped a retro-futuristic narrative about early computing, time travel, and a romance involving a Russian and a Chinese scientist. Here he approaches you with a question: “Have you seen my dad?” You can sense the anguish in his voice. Nina Chanel Abney’s Imaginary Friend hovers mysteriously mid-air and seems to be blessing the surroundings. Darren Bader’s giant girl (accompanied by a lively little dog) carries a crucifix and seems to have wandered out of some religious allegorical painting. KAWS’s easily recognizable figures float in the air as if weightless. So do Olafur Eliasson’s luminous sun and Alicja Kwade’s perpetually rotating figures. And Bjarne Melgaard’s Cheese Man keeps dropping the book he holds before turning gray and fading away. How best to describe their way of existing in the world? Are they virtual hallucinations, digital mirages?

Benjamin’s touchstone essay, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” which addresses photography and film in particular, opens with the words of French poet Paul Valéry: “We must expect great innovations to transform entire techniques of the arts, thereby affecting artistic innovation itself and perhaps even bringing about amazing change in our very notion of art.”5 Valéry was right: photography and film changed art forever. Today we seem to be witnessing yet another transformation. These pioneering AR works do not belong to the era of mechanical reproduction. We are moving beyond that historical moment, entering a new chapter.

With AR, new forms of public art will emerge and new exhibition models will evolve outside of the usual museums and arts institutions. In recent years, works including a virtual reality component have regularly been displayed in exhibitions in ways that obey traditional institutional structures. Could one instead imagine immersive experiences distributed across cities, towns, and continents in novel ways, connecting audiences by creating entirely new exhibition formats? In other words, will immersive technologies like AR change the ways art is presented and make possible new forms of exchange for a potential future in which audiences may be less keen to travel? Can these new modes of presentation solve the sustainability problems posed by shipping art in massive crates in a time of global climate crisis?

“‘But oh!’ thought Alice, suddenly jumping up, ‘if I don’t make haste, I shall have to go back through the Looking-glass, before I’ve seen what the rest of the house is like! Let’s have a look at the garden first!’”6 The Looking Glass begins on the plaza outside of The Shed and continues on the High Line, New York’s popular garden that meanders down the west side of the city. In this public garden elevated above the street on a repurposed freight-shipping rail line, Okoyomon’s magical flowers perform their long poems all day and night. Eliasson has created a virtual garden biotope, inhabited by entities living in another dimension. If you find a real spider or spider web while exploring the High Line, take a photo of it and submit it on the Acute Art app. Doing so will give you access to yet another spider that you can take with you. Place it in your living room, it’s yours forever.

Notes

- Lewis Carroll, Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There (London: Macmillan and Co., 1872), 10.

- Walter Benjamin, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” in Illuminations, trans. Harry Zohn (New York: Schocken Books, 1969), 237.

- “The Third Glass: A Conversation Between Sanford Kwinter and Daniel Birnbaum,” in Johan Bettum and Yara Feghali, eds., Breaking Glass: Spatial Fabulations & Other Tales of Representation (Baunach: Spurbuchverlag, 2021), 14 – 27.

- Ibid.

- Benjamin, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” 237.

- Carroll, Through the Looking-Glass, 24 – 5.